Garden Partners Unite to Save U.S. Forests

-

Country

United States of America -

Region

North America -

Programme

BGCI -

Workstream

Saving Plants -

Topic

Plant Conservation -

Type

Blog -

Source

BGCI Member

News published: 22 June 2022

Author Anna Funk

Twenty years ago this summer, a penny-sized, emerald-green beetle was spotted in North America for the first time. Found not far from the shipping yards of Detroit, Michigan and Windsor, Ontario, it’s suspected the beetle hitchhiked on wooden packing materials from its native Asia. It’d go on to kill tens of millions of trees.

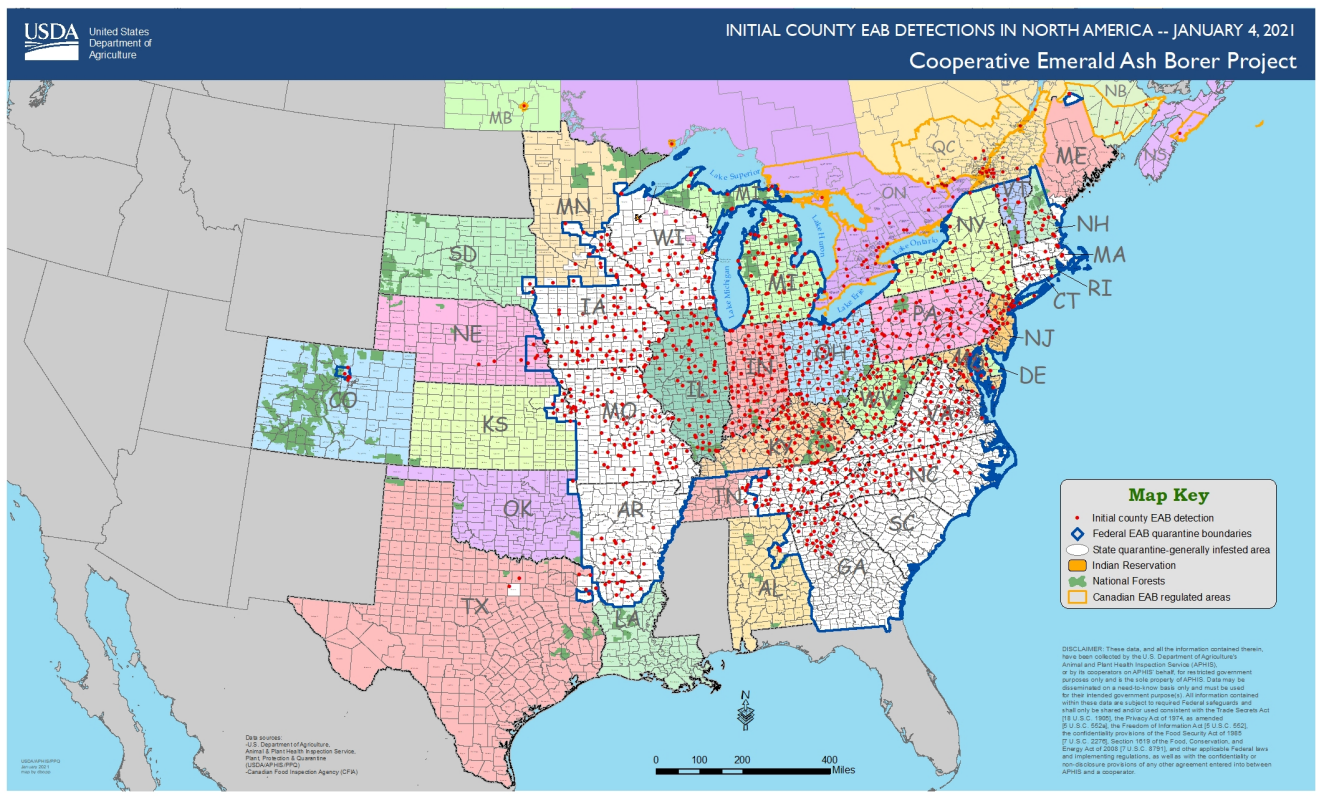

Emerald ash borers lay their eggs in crevices in the bark of ash trees, and their larvae burrow along the cambium, destroying the tree’s ability to obtain the nutrients it needs to survive. In the years since its arrival, the EAB has spread to 35 U.S. states and 5 Canadian provinces, resulting in close to 100% ash mortality in its wake.

Researchers have tracked the decline of ash all along the way, quantifying the speed of the beetle’s spread and the death of infested trees. They’ve watched for impacts in affected forests, watching as newly opened canopy gaps have filled in with invasive species like reed canary grass. But as they tracked the decline of the forests, they also noticed that some mature ash trees were surviving in otherwise-decimated areas. These so-called “lingering ash” could be the key to restoring ash to the landscape.

Lingering Trees

By 2010, forest researchers were searching for lingering ash, tracking them, and testing them for resistance to the beetles. Efforts were led by USDA Forest Service biologist Jennifer Koch.

To test lingering trees for resistance, researchers start with a sample from a forest tree that appears healthy in an otherwise infested area — a branch. Back at the lab, they clone the tree multiple times through grafting, to create saplings for study. Once the trees have grown to a certain height, they add EAB eggs to them directly. After 8 weeks, they can see how the tree has responded by peeling back the bark to view the larvae.

On a non-resistant tree, they’ll find a healthy, 8-week-old larva. In some trees, the larva may appear stunted, demonstrating that the tree has some amount of resistance. In the most resistant trees, the larva will be dead — in some cases, with their feeding line totally hardened over.

Introducing more resistant trees into natural populations could significantly reduce the chance of extinction for ash trees. Biologist Rachel Kappler, now at Holden Forests and Gardens, modeled ash populations in northwest Ohio to estimate the probability of forest health outcomes under different scenarios. Under the worst-case EAB scenarios, introducing resistant trees should reduce the probability of ash extinction by 30 percent, if resistant trees rebound to pre-EAB survival rates.

Watch: Breeding for EAB Resistance: What Does the Future Look Like for Ash Trees?

Finding resistant trees in the wild, though, is just the beginning of the larger breeding and reintroduction endeavor. Once resistant clones are identified, the next steps are to plant them into fields for further testing, cross-pollinating them by hand, and once again selecting the best trees for breeding. When the trees are ready, the seeds will be harvested for planting elsewhere. It’s a massive undertaking.

Great Lakes Basin Forest Health Collaborative

Coordinating this effort today is the Great Lakes Basin Forest Health Collaborative, launched in January 2021 by leaders at Holden Forests and Gardens, the U.S. Forest Service, and the nonprofit American Forests. In addition to ash, the collaborative is currently focusing on beech and hemlock, other important forest trees that are also facing widespread pest threats.

The purpose of the collaborative is to facilitate collaboration across partner groups, sharing resources, workloads, and research updates. Over a dozen partners are actively participating so far, like researchers from the Morton Arboretum working on the development of disease- and pest-resistant cultivars in elm and ash, parks, research institutes, universities, and more. The collaborative offers guidance and training on every step of the breeding process, from tree monitoring to propagation and growing, through both in-person workshops and webinars.

How to get Involved

Anyone in the region can help these efforts by reporting ash, beech, and hemlock trees using the TreeSnap app. Observations help researchers track the spread of pests and identify lingering trees that might be resistant. When you report a lingering tree, researchers with the GLBFHC and the U.S. Forest Service can investigate — each new resistant tree found can increase genetic diversity of breeding efforts, bolstering the vigor of the trees bred in the program.

If you’re in the tree conservation sector in the eastern or central U.S., the GLBFHC is continually adding new partners with interest and ability in:

● Monitoring ash, American beech, and eastern hemlock trees;

● Monitoring the spread of insects and disease;

● Locating potentially resistant individuals;

● Collecting and storing seeds and scions (cuttings);

● Germinating and/or grafting trees; and/or

● Planting trees for research

Contact Forest Health coordinator Rachel Kappler at rkappler@holdenfg.org for more info.

Information in this post from Rachel Kappler.

Support BGCI

You can support our plant conservation efforts by sponsoring membership for small botanic gardens, contributing to the Global Botanic Garden Fund, and more!

BGCI Member Announcement

Are you a BGCI Member? Do you have a news announcement, event, or job posting that you would like to advertise? Complete the form at the link below!